Deep Dive: How Stripe's Paystack is able to offer a consumer app, Zap

The behind-the-scenes story of building a fintech in a controlled market

Welcome to the first edition of Fintech Bridge — a newsletter exploring the bank and PSP partnerships, regulatory licenses, and GTM motions required to launch new fintech products. I’ll share process flows, playbooks, and practical insights from my seven years of experience building and scaling fintech in Africa, the UK and beyond.

For the best experience, view this on a laptop and hit the Table of Contents on the left to jump to the section you care about the most.

1. The behind-the-scenes journey of building a fintech

Your standard opening question regarding fintech licensing is:

What do we want to build? What features are we going to offer?

What licence covers it? That is, what licence list those features as permissible activities in the guideline?

Often, one licence doesn’t meet all of a fintech’s needs. This is expected because fintechs are always looking to maximise capabilities while minimising upfront and overhead costs. Otherwise, they would have acquired a banking licence.

Despite asking the questions above, some of the innovations that fintechs want to bring to the market are not explicitly covered (i.e. prohibited/permitted) by any regulatory guideline. This is what we often refer to as a “grey area”.

As a result, the fintech looks for creative ways to combine bank and Payment Service Provider (PSP) partnerships with an assortment of its licences to deliver its offerings in a way that elicits “no objection” from the regulator.

Interestingly, there is no sure way to know beforehand if the CBN will approve your creativity. Thus, the only way out is through it — report yourself to the CBN and get their feedback on your offering.

Early-stage startups are more wary about speaking to the CBN first for fear of being restricted before proving their hypothesis. But later-stage startups often prefer this approach. In any case, their existing business requires them to be in touch with the regulator, and they have too much to lose (reputational damage, heavy fines, etc) if things go south.

Over the years, many fintechs have come and gone, possibly offering the service your fintech wants to offer. But no repository of knowledge shows their interaction with the CBN as a precedent for you to follow. Plus, for non-codified guidelines, a change in the CBN leadership or department director can mean previous practices and concessions will no longer hold.

This 1:1 model of having to speak to the CBN yourself impacts four parties:

You, as the fintech. Your interaction with the regulator forms part of your “trade secret” in how you bring a product to the market. It also makes you less likely to make important disclosures to your customers, even when they are mandated by consumer duty laws.

The customer. Finds it harder to separate rogue players, who could be shut down at any time due to regulatory infractions, from genuine players. They will need to read the fine print in terms and conditions, or website footers, to gain clarity over what legal entity is providing them a service, and the liability to the customer.

The competitor. Can’t achieve a level playing field to roll out similar services because you do not know how your competition can go live with such service (s), given the perceived ban or greyness of the area. You work with tons of consultants and law firms, yet everyone seems to be saying a different thing because they are all speaking from their own specific and often limited interpretation of the law, which arose from a 1:1 interaction with the regulator.

The regulator. Being mystical seems to be a feature of regulators. It helps weed out unserious players, but also, the secrecy of interactions with applicants could serve as a breeding ground for underhanded practices like bribery and corruption.

What further complicates this situation is the fact that sometimes, a single offering (for instance, holding customer funds, i.e. issuing dedicated wallets or accounts ) can be powered by several licences. For instance, in Nigeria, the ability to hold funds, on the surface, can come from a plethora of licenses backing. Fund-holding licences include MMO, MFB, PSB, and a DMB (commercial) licence. However, the distinction is in how those funds are accounted for and protected by laws like deposit insurance.

But does the customer care? All they care about is that they can share their account details and receive and hold money in that account.

After asking what features, licences, and regulatory approaches will cover your impending product. The next thing is WHO.

Who are we going to offer this service to?

That is, who are we going to onboard (individuals or businesses)? Where are they residing or incorporated? And what laws govern selling to people there?

Typically, this question gets answered in the licensing decision-making phase. But sometimes, it needs to be further blown out, if it wasn’t clear.

Now that we know this, let’s get into what Zap does and what the above process might have looked like for them.

2. What does Zap do, and who does it serve?

Following our BTS story, let’s start by defining what features Zap offers.

Zap can:

open local bank accounts,

receive payments,

hold funds in naira, and/or

make domestic payments,

for:

Nigerians, and/or

Visitors to Nigeria

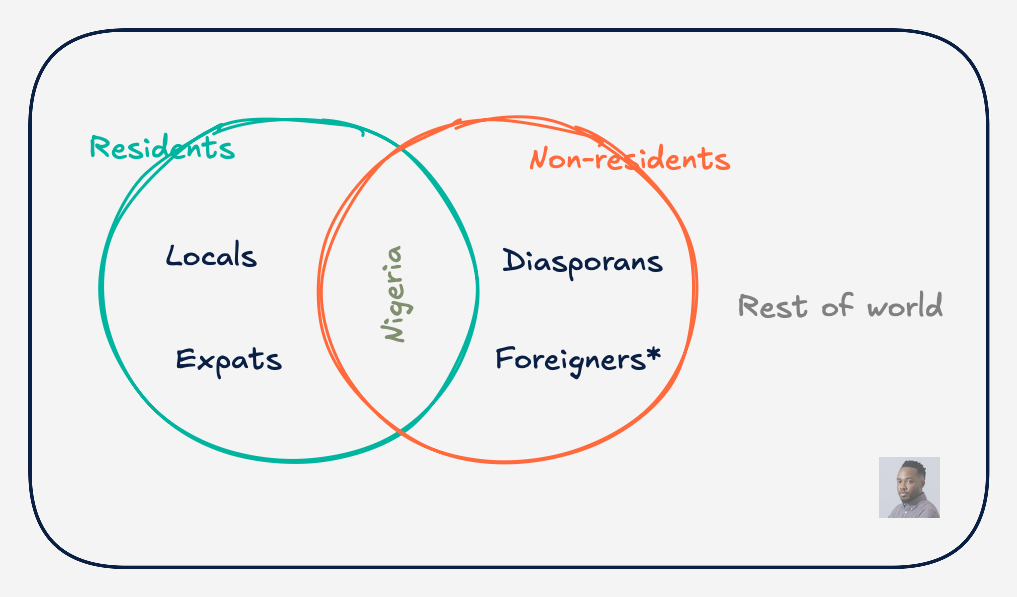

Figure 1 shows Zap’s intended audience. The green circle is a set containing potential users who are residing in Nigeria. They include: Nigerians living in Nigeria (locals), foreigners with residence permits, either because they are expats or Directors of a Nigerian company.

The orange circle is a set of non-residents who want to make payments in Nigeria. They include Nigerians (by nationality) in the diaspora and foreigners who secure temporary visas to visit Nigeria.

In all cases, except for non-resident foreigners, those users are eligible to open a bank account in Nigeria because they can obtain a Bank Verification Number (BVN). So, Paystack’s Zap will be able to use that BVN to issue, at least, Tier-1 (lowest tier) bank accounts to them.

Other individuals not captured by the Venn diagram are out of scope. For instance, someone in Pakistan (a non-resident individual with no business with Nigeria) is not a potential Zap user, at this time.

3. How does Zap compliantly perform its functions?

While section two states Zap's functionalities, we need to consider some other fringe aspects of operating an app in a highly regulated space.

But first, let’s go through the customer journey of someone trying to use Zap.

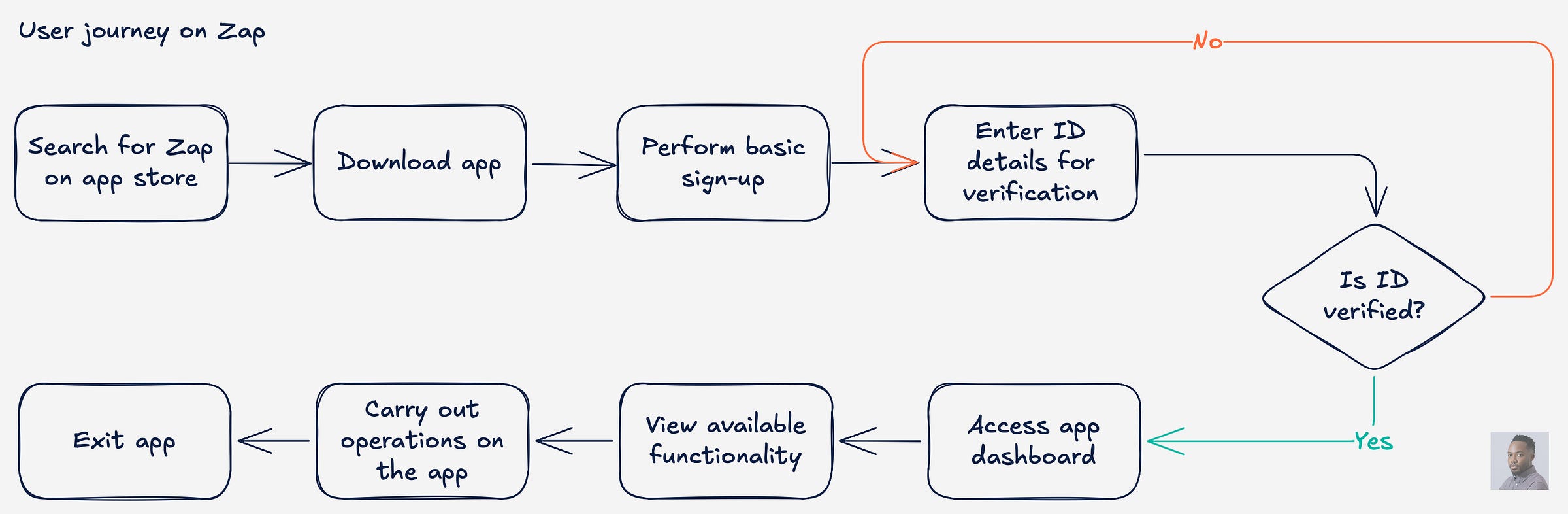

The journey starts with app discoverability and access, before moving to onboarding (ID verification in line with KYC/AML requirements) and ultimately, feature access and usage.

Financial services providers typically:

Make their apps/services available in target markets where they are sure of their compliance and legal standing. That is, they have an explicit licence to offer such a service from the financial services regulator there or do not need a licence for that service. For instance, in the US, Montana doesn’t require fintechs offering money transmission services to register as MSBs. So, a global fintech can be confident of onboarding Montana residents. While in New York, such a fintech can make its app inaccessible to residents to avoid regulatory headaches.

onboard users from only eligible jurisdictions. Thus, they intentionally exclude users from certain regions like high-risk jurisdictions, et al. For instance, assuming the fintech could onboard users in Montana but somehow, that part of the US is flagged as a high-risk zone (which is not typically how it works, it’s on a country-level basis), the fintech can decide to completely abandon Montana as an expansion market or proceed with caution, via things like Enhanced Due Diligence (EDD).

throttle features based on their assessment of a customer profile. Here, the fintech is approved to operate in Montana and their home market, but might limit the features available to customers in either market based on their internal reasons, or other legal and compliance reasons.

App availability

I do not know how many countries Zap is available for download in. But I know at least one market other than its home market (Nigeria), where it’s available for download, and that’s the UK.

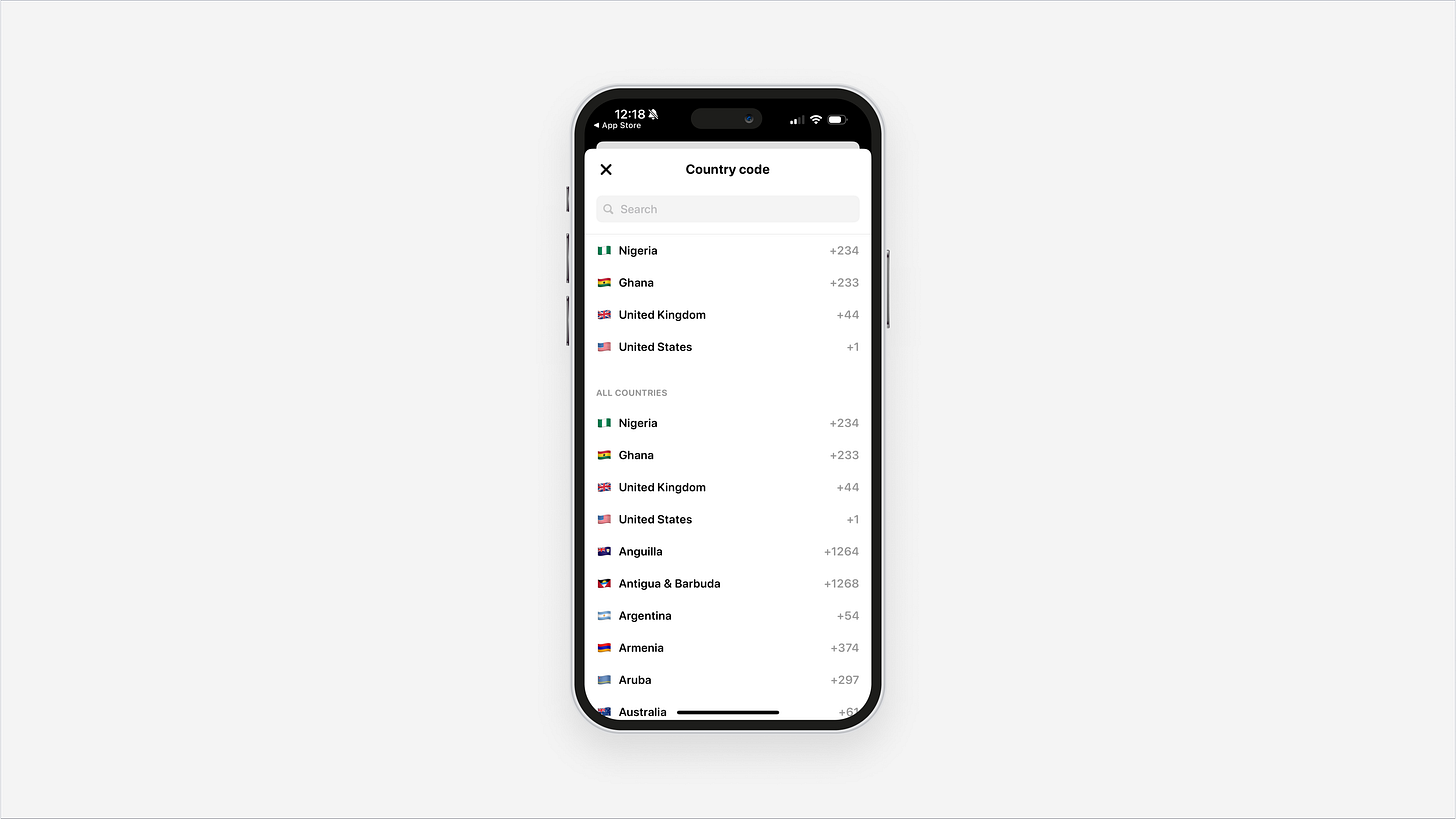

Also, using the “Enter your phone number” drop-down as a weak proxy, one can imagine that Zap is currently available for download globally but expects most early(?) users to come from four countries: Nigeria, Ghana, the UK, and the US.

Onboarding

To onboard customers, they have to know about your business. They can know about your business either through your direct advertisement to them or their independent explorations.

To directly target customers in a particular jurisdiction, a business will have to check if the service they are providing is regulated (payment is a no-brainer). If it is, they will need to get the regulatory licence before advertising their services, otherwise, they could run into trouble. However, if the latter is the case, and a resident finds your service via their exclusive initiative. Then, you are in a grey area as many markets accommodate “reverse solicitation” (EU), “passive availability” (UK) or equivalent, if you can prove it.

Reverse solicitation, also known as reverse enquiry, refers to circumstances in which a prospective client approaches a regulated financial services firm at its own exclusive initiative and requests services and/or products from that financial services firm.

…

However and rather importantly for third-country firms, even where a client has initiated a business relationship on the basis of reverse solicitation with that (third-county) firm, that firm cannot offer further services to an EU/EEA client other than those that the client had requested of it.

— PwC (2022)

Paystack’s argument that it’s targeting Nigerians (and visitors to Nigeria) is strong:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Fintech Bridge to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.